In the News

Below are just a few examples of the new coverage that WHPR has provided their clients. Contact us today to see how we can help your organization.

-

Out of the Box

(Client: Credit Management Association)

Out of the Box

By RICHARD CLOUGH – 11/2/2009

Los Angeles Business Journal StaffIn 2000, Matco United Inc. was on the brink of failure.

But rather than file for bankruptcy, the paper company, hemorrhaging cash after a disastrous change in management, tried something different.

Chief Financial Officer Daphne Mason had heard of a little-known process called a “general assignment for the benefit of creditors,” a process similar to bankruptcy but which was supposed to be quicker and less costly. So she enlisted Credit Management Association, a Burbank non-profit, to carry out the procedure.

“It was wonderful,” she said. “They were very organized. They were able to sell our inventory off in a matter of weeks.”

CMA, which counts some 1,600 member companies, provides support for credit managers, who oversee customer credit and receivables, by offering continuing education and services such as lien filing.

But the majority of its revenue is derived from general assignment work, which in a nutshell functions like an out-of-court bankruptcy proceeding. A failing company will transfer control of its assets to CMA, one of just a handful of general assignment handlers in the state, which will then negotiate repayment plans with creditors, liquidate the assets and distribute money to creditors.

The benefit is that the process can be done without the added expense of attorneys or the time-consuming process of obtaining court approvals, said Mike Joncich, who manages general assignments for the CMA.

“The process moves much more quickly and often times more smoothly than in bankruptcy court,” he said. “Our expenses then, understandably, are much lower than a bankruptcy process (and) we get essentially the same results.”

The association earns money by taking a fee that is typically a percentage of the assets it liquidates.

General assignments are allowed under an obscure provision of the California code of civil procedure, which is one of the friendliest to general assignments, according to Joncich. For example, the law allows assignees to remain in a landlord’s premises for a period during the liquidation process, which is not guaranteed in many other states.

Not surprisingly, the association’s general assignment business has picked up as of late as greater numbers of companies go out of business. Bankruptcy filings tend to be a lagging indicator to the general economy.

“Right after Labor Day the phones started ringing and they haven’t stopped,” said Joncich, who expects the association to handle about 200 general assignments in 2009, nearly double last year’s total.

Tough times

The association also takes general assignment cases from nonmembers. To handle the business, Joncich recently brought in a new hire, and he anticipates additional growth.

“I expect that after the first of the year we’ll get another surge and after tax time we’ll get another surge,” he said.

That increase is a bright spot in an otherwise difficult time for the association. For the past several years, the organization’s membership base has been shrinking at a rate of about 1 percent a year.

Chief Executive Michael Mitchell said many businesses have been eliminating credit manager positions, noting that “companies are looking for anywhere to make cost cuts.”

CMA was born, in a sense, some 126 years ago.

In 1883, a group of local business owners formed the Los Angeles Board of Trade to promote business activity and help business debtors. The board, which would later give rise to the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, eventually merged with the Los Angeles Credit Men’s Association to create the organization that would later be known as Credit Management Association.

CMA has remained a non-profit organization because Mitchell said it helps it maintain its focus on supporting its constituency. Today, just one-quarter of the association’s 60 employees works in the adjustment bureau – the unit that handles general assignments – but general assignments account for roughly two-thirds of CMA’s income.

While the liquidation can often be completed in a matter of months or even weeks, Joncich said a typical case takes about a year. The association not only will liquidate a company’s assets, but even erase telephone numbers and domain names.

Many of the assignments CMA handles are small, but in 2003, the association liquidated nearly $20 million in assets of Indian Motorcycle Co. of America, a motorcycle manufacturer in Gilroy that went into receivership. The name was sold to a company that has since resumed manufacturing.

Business owners often like general assignments because they can shut down their business and walk away without the stigma associated with having filed for bankruptcy, Joncich said.

Indeed, one business owner reached by the Business Journal who had liquidated his company through general assignment declined to comment on the record because he did not want it known that he was forced to shutter his business.

But since the process is not public, creditors are sometimes skeptical that they will get fair returns. They can try to block the process by filing a petition of involuntary bankruptcy to put the case in U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

“A lot of it depends upon the cooperation of large creditors,” said Byron Moldo, a bankruptcy attorney with Ervin Cohen & Jessup LLP in Los Angeles who has acted as an assignee on general assignments. “If a secured creditor is not cooperative and not willing to go the assignment route, it can be very, very difficult.”

In the case of Matco, CMA took control immediately, relieving company officers of their positions and liquidating the assets.

CFO Mason said she was impressed by the efficiency. “We were able to capture over 95 percent of our receivables.”

The biggest battle for CMA is simply educating people that general assignments exist. Many are unaware, Joncich said, including even some attorneys.

“That’s one of my frustrations,” said Joncich, who came to CMA 14 years ago after working for a bankruptcy trustee. “Companies that are going out of business of course don’t know what all their options are. Business failure is not something that most business people pay much attention to until it’s facing them dead on.”

Credit Management Association

Headquarters: Burbank

Founded: 1883

Core Business: Assisting credit managers and companies with business credit functions; handling general assignment liquidations

Employees: 60

Goal: To grow its membership base

Numbers: Expects to handle 200 general assignments in 2009, nearly twice the amount of 2008

Los Angeles Business Journal, Copyright ©2009, All Rights Reserved.

-

Last Stand for Newsstands: Read All About It

(Client: Farmers Market)

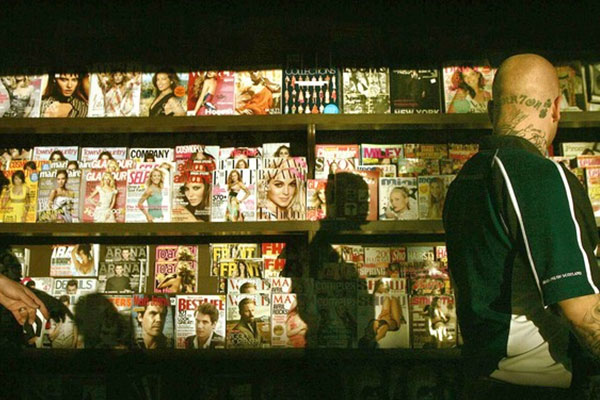

A customer checks out the racks of magazines at World Book & News in Hollywood. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times / February 27, 2008)

Ink-stained holdovers such as Sheltams at the Farmers Market still cater to a loyal if shrinking coterie of tradition-bound customers.

By James Rainey

October 28, 2009It’s the month that Condé Nast folded Gourmet and a couple of other big-name magazines, the week that newspapers reported tanking circulation, again, and the day that hundreds of micro-bloggers gathered in Los Angeles to celebrate a world of tiny messages on glowing screens.

So here I am at the Farmers Market in Los Angeles, in the midst of a bunch of folks who didn’t seem to get the message: Ink on paper is dead.

There’s actor Mario Roccuzzo, camping with a newspaper at his usual spot in front of the lottery screen. Eduardo Cervantes hurries in to grab the L.A. Times and La Opinión, looking forward to perusing the news on a break from his deli job. Makeup artist Jacki Shepard stands, mesmerized, in front of a thicket of plush fashion magazines. Yes, she said, Vogue Italia is worth the $22 price tag.

Sheltams Farmers Market Newsstand is one of the social nerve centers within the 75-year-old Fairfax Avenue market, a place where some regulars have been coming for decades — to see their friends, to share a little conversation or a political argument and, yes, to buy a newspaper or magazine.

In a time when other venerable newsstands — such as Universal News in Hollywood and Bungalow News in Pasadena — have been driven out of business, the Farmers Market location is staying alive as it embraces the old and tries to adjust to the new.

You can still while away an afternoon thumbing through the rows of magazines, with no one hurrying you along. You can still commiserate with friends over your Lotto winnings. Or you can buy a fancy cigar and order up a reprint of an overseas paper from the computer humming in a back room.

As of June, owner Paul Sobel became the first retail outlet in Los Angeles to offer NewspaperDirect, an online service that provides access to 1,133 titles in 40 languages. The Farmers Market Newsstand will print a copy of any of them, while you wait, for $5 weekdays, $7 on Sundays.

“We still are a vital purveyor of newspapers and magazines. We’re still relevant,” Sobel said. “But we need to find new ways to maintain that equilibrium. That’s why we’ve started the downloading of printed papers.”

Sobel said he had to find a way to fill the void, because prohibitive shipping costs meant he could no longer obtain many foreign and even U.S. papers.

Based on the few hours I spent hanging around Sheltams (named after Sobel’s sisters, Shelley and Tamara), the on-demand papers have a long way to go to become as popular as the Mega Millions lottery.

But Sobel said he realized, after 34 years at the Farmers Market, that he had to “find a way to bridge the technological divide and provide a service customers want.”

Myriad pressures make it more difficult than ever for a newsstand to succeed. Wholesale publication prices keep going up, while the public’s disposable income seems to keep going down. Chain bookstores can undercut independents on price.

Sobel once had stands in six L.A.-area locations, including a second Farmers Market outlet, which he closed in April.

Many younger readers, in particular, seem content with the news they can read on their cellphones. At the 140 Characters Conference in Hollywood on Tuesday, micro-bloggers discussed how they can sweep the world with 140-character Twitter messages.

That all seemed a world apart from the old newsstand and regulars like Roccuzzo, the actor, who has been a mainstay here since his old haunt, Schwab’s in Hollywood, closed in 1983.

“I call this my office,” he said. “I’m here twice a day, almost every day.”

Roccuzzo, who played hundreds of character roles over half a century in the business, said he is “not a computer guy. . . . This is our world and we love it.”

The world is a shopworn corner of the Farmers Market, just off the parking lot and adjacent to a produce stand, with newspapers and magazines crammed alongside paperback bestsellers, graphic novels and a small tobacco humidor.

The bulk of the customers seem to come for lottery tickets, so many that the tiny outlet was the California Lottery’s retailer of the year in 2008. The regulars still buzzed this week over the $566,000 jackpot pulled down this month by an actor who lives at the nearby Park La Brea complex.

But another crowd of die-hards come here to browse the shelves, which carry everything from Bow Hunter to Auto Trader and the Long Beach Press-Telegram.

Monica Hayward of Santa Barbara drops in regularly when her husband is in town on business. She said a computer screen or printout will never replace the glossy photographs and stories of the Spanish-language magazine Hola! she was taking home.

Shepard said her visits to the newsstand are about exploration — finding new titles or fashion looks she hadn’t discovered before.

“It’s getting out and being in the world and seeing things and other people,” said Shepard, eyes covered in bubble shades, her hair a sharp red wedge. “It drives me crazy no one wants to do that anymore.”

Esther Vinokur, 66, enjoys the friendly ribbing she takes from Sobel. “Paul asks me, ‘If you ever win [the lottery], what will you have to complain about?’ ” laughs Vinokur, who came to the Fairfax district when she was a teenager. “It’s very haimish here, it’s homey.”

The newsstand crowd trends toward middle or retirement age. But more than a few younger readers said they too can’t abide a world that’s all about computers and cellphones.

“I read the paper all the time and I don’t have an iPhone. My friends call me caveman,” said Tom Ptasinski, 24. “On the Internet there is just so much information. Click here. Pop up there. Stuff’s jumping in front of you all the time.”

Ptasinski, who types transcripts for the “Dr. Phil” show, said he gets enough computer time at work.

“With my paper, I can take it with me. I can read it when I want. I can enjoy it when I want,” he said. “Maybe I am just old-fashioned.”

-

Lessons from the Lean Years

(Client: Credit Management Association)

Tough times can provide a great opportunity to improve your company’s bottom line. Here, four financial strategies that may help to position your small business for long-term success. As your business emerges from the long, punishing downturn, you probably feel you could get through anything. And you just might be right. More than half of Fortune 500 companies – including such icons as Kraft, ExxonMobil, Disney and Microsoft—launched during a recession or a bear market. Whether businesses are new or well-established, those that find ways to cope—or even thrive—when times are tough may be better positioned to surge ahead of the competition once the economy takes off. The strategies below not only can help you get through the near term, but they also may give your company an enduring edge.

As your business emerges from the long, punishing downturn, you probably feel you could get through anything. And you just might be right. More than half of Fortune 500 companies – including such icons as Kraft, ExxonMobil, Disney and Microsoft—launched during a recession or a bear market. Whether businesses are new or well-established, those that find ways to cope—or even thrive—when times are tough may be better positioned to surge ahead of the competition once the economy takes off. The strategies below not only can help you get through the near term, but they also may give your company an enduring edge.Look first at payroll and benefits

In any downturn, it is critical to keep business costs in check. But even the healthiest businesses can benefit from some cost-cutting measures.The biggest expense is frequently payroll and benefits. Look at areas where you can cut excess spending or where you can consolidate or simplify processes. For example, consider the cost of retirement plans. If profit sharing or a 401(k) is part of your benefits package, review your plan provider’s fee schedule. “Ask yourself what services and features you’re paying for and whether you’re using all of them,” suggests Michele Wickles, Managing Director and Product Management Executive, Bank of America Merrill Lynch. “Working with all your resources to optimize the services that you are paying for can be to your great advantage.”

Decreasing the company contribution to employee benefits is another potential source of immediate savings. You might consider asking workers to kick in more—paying 25% of health insurance premiums, for example, instead of just 10%—or you could reduce the amount you contribute in profit-sharing dollars or matching funds to a 401(k). You should explain these changes as necessary—and possibly temporary—moves to help shore up the company’s financial health. Tread carefully, though. “If you’re taking a benefit away, it’s important to emphasize that it’s so the business can stay the course,” says Wickles. “That’s to everyone’s advantage.” It is better to invest the time upfront to build employee support for changes than to risk leaving people in the dark and damaging both productivity and morale.

Payroll is also a category where you can find major savings. Evaluate whether the cost of your employee wages aligns with your business profits. Staff reductions are usually the most obvious way to lower the expense of salaries. But if your workforce is already lean, doing this can place stress on both your employees and your business’s ability to meet customer needs. As an alternative, you may want to consider transferring a larger portion of your sales staff’s pay to commission. This alteration to your business model allows you to incur additional expense only if employees sell more, and could create a lasting cost advantage. While introducing this change to employees requires careful handling, your staff may find it preferable to layoffs and a strong motivator to improve performance and bring in more revenue.

Streamline your expenses

Not every financial move has to revolve around your staff costs, however. Small cuts can often make a big collective difference. Look at every item, line by line, to see where you can trim. If your company buys raw materials, consider switching to less expensive suppliers or inviting existing suppliers to rebid for your business. If your firm relies on service providers, explore creative pricing strategies. For example, look for situations where you can get several services bundled together at a combined lower price or where you may be able to get a discount for a long-term contract. Phone and Internet providers usually offer both options. These basic services may seem like obvious examples of areas to save, but for many businesses they are large sources of empty spending.“The real opportunities for cutting costs in a small business tend to be with recurring expenses: utility bills, Internet service, subscriptions, insurance,” says Bruce Pounder, chair of the Small Business Financial and Regulatory Affairs committee of the Institute of Management Accountants. “Maybe your phone bill is bigger than it has to be because you signed up for 100 voicemail boxes and need only 50.” His advice: “Don’t write a check without asking, Can I get this cheaper elsewhere? And do I really need it at all?” Paring down these bills and putting firm cost controls in place now will bolster your profit margin once sales start to rise again.

Master the art of cash flow

It’s easy to become lax about collections when the money is rolling in, but tough times offer a great chance to tighten your billing and payment practices.

First, see if you can negotiate better terms with your vendors, such as a longer payment schedule or lower interest rates. Keep in mind, however, that your leverage may depend on your company’s size and importance to the vendor. Vital customers tend to have more leeway in negotiating terms.

Apply similar scrutiny to the money that customers owe you. If sales are stagnant and receivables are growing, that probably means that people are taking longer to pay. Mike Mitchell, president of the Credit Management Association, suggests devoting more staff time to calling delinquent accounts. And don’t wait until payment is 15 or 20 days past due. On day one, make the call. Finally, consider getting outside help so that you can collect more effectively and continue to focus on your core business. A collection agency may seem like a draconian step, but you can instruct the agency to go easy on clients at first and to couch efforts as “reminders,” not threats. The payoff of freeing up funds is likely to be worth it. Only companies with sufficient cash flow in good times and bad can pursue possibilities for innovation and growth.As you evaluate strategies for addressing challenges caused by the downturn, consider asking your Financial Advisor these questions:

- How might I fine tune the costs in my business retirement plan?

- How can we estimate the impact of a shift to a commission-based payroll?

- What other areas of my business should I examine for potential cost-cutting measures?

- What types of lenders would be most appropriate for my business?

-

Trade Creditors Play a Key Role

(Client: Credit Management Association)

October 10, 2009. Letters to the Editor, LA Times

Re: Economy is growing again.

The news that the US economy returned to growth may signal the technical end of the current recession, but sustaining real growth demands support for trade credit.

Federal policy and bank practices must empower businesses that manufacture goods on the promise to pay their suppliers when those goods are sold. These trade creditors make more than half of our economic activity possible and they generate jobs that build sustained economic strength.

Yet economic policy continues to focus almost exclusively on secured credt. When banks receive federal funds but fail to move those funds to Main Street and industrial parks, too many businesses languish and too many people remain unemployed.

When the headlines say “Job market is growing again,” it will be because the vast network of trade creditors finally got the support and attention that a smart economic plan requires.

Mike Mitchell

President

Credit Mangement Assn.

Burbank -

Credit Debate Needs to Get Down to Businesses

(Client: Credit Management Association)

By MIKE MITCHELL and RICHARD HASTINGS

As the small business center of California, Los Angeles drives the largest economy in the United States.

The economic engine in our region is remarkably deep and wide – high-end restaurants, hotels and garages, gift shops and grocery chains, small and medium manufacturers and retailers, and a virtual catalog of other enterprises – and it all depends on a system of business-to-business credit that is absolutely vital.

Elected officials and policy makers in Washington are ignoring that system of credit. Leaders in Sacramento don’t even talk about it. Until their focus shifts to business-to-business credit, our economy will not heal.

The L.A. economic system, much like the rest of the American economic system, is based on a strong and resilient foundation of faith and trust between free merchants who engage in unsecured business-to-business credit, otherwise known as trade credit. This credit moves goods and services, and it relies on trust that invoices will be paid after a brief period of time – a period that we call credit. Credit derives from the Latin word for trust and when that trust is broken, the entire system suffers unfortunate consequences.

Unlike consumer credit, business-to-business credit paves the roads under the trucks that carry the goods from the Port of Los Angeles to farms, factories, distribution centers, retail stores and small businesses.

When Joe Smith makes tables, he purchases raw wood. Joe buys that wood on credit from the wood supplier. He gets about a month to pay for it. No special security is required, unlike the mortgage on your house, secured by the property on which you live. Joe enters into purchase order agreements with retailers who want to buy his furniture on unsecured credit terms; typically, they pay Joe at least a month after he ships them the furniture. He trusts he will get paid. He has to get paid, or his wood supplier won’t get paid and may not get new orders from Joe if Joe’s customers do not pay him.

Running tables

Joe’s tables are important. His employees earn their wages making his tables, the truck drivers who deliver his products to retailers depend upon Joe and the retailers make their profit only when they sell Joe’s tables. All those jobs feed the economy so families can purchase tables or chairs or countless other products. This is a beautiful, complete circular flow of commerce, but if one component breaks down, the entire flow can break down, leading to lower wages, lost jobs and a weak economy.You get the picture. Business-to-business credit literally creates the kitchen table around which families sit each month to pay their bills and figure out what they’ll spend. However overworked the image may be, the American economy rises and falls around that table.

We applaud lawmakers and policy makers in Washington and New York for taking steps to improve the banking and regulatory systems. We sincerely hope that leaders in Sacramento can overcome their legendary bickering and devise a rational, compassionate way out of the mess that is our state budget. At the same time, we offer a stern warning. Until and unless overall trust is restored (and liquidity is a function of trust), no matter what policy makers do, the economy will continue to lag and the recovery will take that much longer.

-

75 Years of the Original Farmers Market

(Client: Farmers Market)

“Los Angeles is a very impersonal town,” says Bob Tusquellas. The Original Farmers Market “is the opposite of that,” says the merchant, who owns Bob’s Coffee and Doughnuts, Tusquellas Seafoods and Tusquellas Fish and Oyster Bar. The market is turning 75 this week, with a celebration that includes the USC marching band, dignitaries and a cake shaped like the market’s clock tower.

Time moves a little slower at the much-loved gathering spot at 3rd and Fairfax. For longtime merchants and old friends, it’s a respite from a hurried world.

By Mary MacVean

July 15, 2009When his favorite breakfast spot at the Original Farmers Market switched from metal to plastic cutlery a few years ago, longtime regular David Freeman didn’t.

Instead, the Los Angeles writer brought a spoon from home. Once he finishes his morning coffee, he returns the spoon to the market’s tiny Coffee Corner to keep for him until his next visit.

“Los Angeles is a very impersonal town. This is the opposite of that,” explains Bob Tusquellas, who owns Bob’s Coffee and Doughnuts, Tusquellas Seafoods and Tusquellas Fish and Oyster Bar.

Freeman echoes the thought: “I didn’t realize I would someday value the simple act of knowing the person who makes my coffee.”

At its beginning, a few farmers hawked produce from their trucks. Today, the market has grown into a collection of several dozen shops and restaurants at the corner of 3rd Street and Fairfax Avenue. Parking can be maddening. The rickety wood-and-metal chairs are not so comfortable, though plenty of people occupy them for hours at a time, day after day. Some of the shops are remarkably anachronistic, especially compared with the thoroughly modern Grove shopping center next door. Farmers Market merchants have operated for decades on month-to-month leases; some stalls post “cash only” signs.

An estimated 3 million people visit each year, drawn to a place that straddles stodgy and funky, hokey and hip.

Early mornings belong to the East Patio.

At 6 a.m., three hours before the Farmers Market officially opens (though Du-par’s restaurant is open round the clock), the day has begun at Bob’s, where a baker rolls out loaf-sized pillows of dough and cuts out dozens of circles, deftly popping out the hole before placing them on a rack to proof and then fry for raised, glazed — the top seller.

Soon, Phil’s Deli & Grill comes alive, with five workers behind the counter and six people ordering breakfast, including some in red T-shirts that pledge their love for Drew Carey – a ploy to get on “The Price Is Right” next door at CBS.

By 9, the tables fill up. At one sits a trio of women who started dropping by as young mothers, after dropping children off at nearby Hancock Park Elementary School.

“We used to discuss kids and then teens and now it’s parents and grandchildren,” says one of them, Katie Ragsdale.

“Each group believes it’s their place,” says David Hamlin, author of a new book, “Los Angeles’s Original Farmers Market,” written with Brett Arena, archivist for the A.F. Gilmore Co., the family firm that owns the market.

And, in fact, it is their place, at least for a little while.

“Do you know who we are? . . . That is the inventor of the Ponzi. . . . This man invented coffee. . . . We’re not friends, we’re outpatients.”

So begins a conversation — or perhaps a performance — at what must be the funniest, and the most frequently quoted, table in the market. Asked how long the fluctuating group of six to 10 people has been meeting, one says 30 years. In a flash, another adds, “I got here Thursday.”

At the table one recent Wednesday morning are Freeman, who included the market in his 2004 novel, “It’s All True”; director Paul Mazursky and actor Jack Riley, who has been in dozens of films and TV shows (think Elliot Carlin on “The Bob Newhart Show” and Stu Pickles in “Rugrats”).

They move quickly through the news of the day. They talk about movies and food, “and pray that we stay alive another day. Our medical reports are extensive,” Mazursky says, listing a four-way bypass, strokes and trouble walking among their ailments.

Despite it all, “we are obsessive about coming here. We feel compelled to come here,” he says.

By midday, many of the East Patio regulars have come and gone. Tourists and workers from the neighborhood are out for lunch. People roam from stand to stand reading menus for Italian, Mexican, Malaysian, deli, Middle Eastern, barbecue, sushi, Chinese and more. There’s English toffee that “is its own food group,” says Jimmy Shaw, owner of the popular Loteria Grill Mexican food stand. There’s homemade horseradish and ice cream.

“On a hot day, when the temperature is just right and the smells are blowing in just the right direction, it’s like I was 6 years old,” says Stan Savage, the 36-year-old market manager and great-great-grandson of company founder A.F. Gilmore.

There are shops that seem out of step in an Abercrombie-dominated world. Treasures of the Pacific sells scarves and shells and wind chimes. Others sell stickers, a thousand kinds of hot sauce, souvenirs and toys (none of them electronic games). Shoppers can watch candy being made at Littlejohn’s, or butchers or cake decorators at work. Teenagers on summer break roam between the market and the Grove.

Before its neighbor opened in 2002, the market was a bit down on its luck, but among its virtues was plentiful urban parking. Its fans feared the new, fancy neighbor — validated parking? Oh no! (Despite 4,100 spaces at the Grove and the Farmers Market, parking these days is no amateur’s game, and it can suck some of the serendipity from a visit.)

But the Grove has turned out to be something of an enabler, making the market more authentically itself in the shadow of J. Crew and the American Girl stores.

The Grove also brought a new younger crowd, fans of the newer bars and restaurants such as Loteria.

A century ago, there were no crowds on the Gilmore land at 3rd and Fairfax. Arthur Fremont Gilmore owned 256 acres of dairy farm, and at the turn of the century hit oil while drilling for water. Soon his farm became the Gilmore Oil Co. Over the years, the land has been home to an 18,000-seat sports stadium (where CBS now sits), a baseball field and a drive-in movie theater. In 1934, during the Great Depression, partners Roger Dahlhjelm and Fred Beck suggested that Arthur’s son, E.B. Gilmore, allow farmers to drive up and sell produce. Eighteen merchants came, paying 50 cents a day in rent.A businesswoman saw promise on that dirt lot.

Blanche Magee, who with her husband ran a deli at the Grand Central Market downtown, started feeding them sandwiches. Magee’s Kitchen became the first market restaurant and still sells sandwiches — including a lauded hand-cut corned beef, along with horseradish that brings tears to your eyes — and other foods from a counter run by Blanche’s daughter-in-law, Phyllis.

In less than a year, the trucks were replaced by wooden stalls.

Situated close to Hollywood and Beverly Hills, the market has long been a place where haute and homey mingle.

James Dean supposedly ate his last breakfast here. In a photograph, former President Eisenhower looks at the machine that grinds peanut butter at Magee’s House of Nuts (yes, the same Magee). The Beatles visited. An appearance by Shirley Temple was so crowded that the fire department carved a hole in a roof to lift her out.

The tables and chairs have looked the same for decades. Parents work with children in at least a dozen businesses. Lilian Sears bought the Coffee Corner from her former boss. Clinton Thompson came to work as a delivery guy at the Gumbo Pot and 14 years later bought it from his boss.

Bob Tusquellas started working at the market 56 years ago as an 11-year-old helping slice bacon and wait on customers at his dad’s shop. Today, his customers see him behind his counter, and they see him at a table with his daughters or grandchildren.

“My dad’s philosophy, and it’s mine too, is that the owner has to be there,” he says.

“They know there’s a Bob.”

As sunlight fades, the market crowd grows younger, gray hair becomes blond or black. Grove shopping bags replace walkers, short-shorts replace knit slacks. People fill the West Patio — home to E.B.’s Beer & Wine, a bar named for Earl Bell Gilmore — for a rambunctious karaoke contest.

Lindsay Sherman, 26, and Joseph Hizon, 29, come to sing. Sherman’s husband, Michael Owen, and a friend, Diana Cruz, cheer them on. They all work at CBS and frequent the market.

“Every time we have guests, this is the first place we bring them,” Sherman says.

On Thursday, the USC marching band, dignitaries and a cake shaped like the market’s clock tower will help celebrate 75 years of not-very-much change for this Los Angeles icon. (The official ceremony is from 8 to 9 a.m., with music and entertainment from noon to 10 p.m.)

Not that time stands still. Stan Savage has some plans: he’d like to add a traditional Italian deli. He’s working on parking and on the market’s green practices. He brought farmers back; they sell their produce Fridays and Saturdays.

These things take time, he says, not without affection. “We don’t move quickly on anything.”

And that may be the market’s formula for success.

-

Coffee and the Morning Kvetch at L.A. Market

(Client: Farmers Market)

A bunch of people meet for breakfast every morning at the Original Los Angeles Farmers Market. Quite a few bunches, actually.

A bunch of people meet for breakfast every morning at the Original Los Angeles Farmers Market. Quite a few bunches, actually.Some shopkeepers meet over coffee, some of the drivers who deliver food meet at another table. And then there’s a table at the center where the same group of people, refreshed by an occasional visitor, laugh and kvetch over coffee and the donuts that their doctors say they shouldn’t have.

“It’s just a bunch of shmoes in the picture business meeting in the morning for coffee,” screenwriter — and fellow shmoe — David Freeman says. “You blink and it’s 25 years later and people come from all over the world to sit here. I don’t know why.”

Host Scott Simon pulls up a chair to find out.

-

A Literary Legend Fights for a Local Library

(Client: San Buenaventura Friends of the Library)

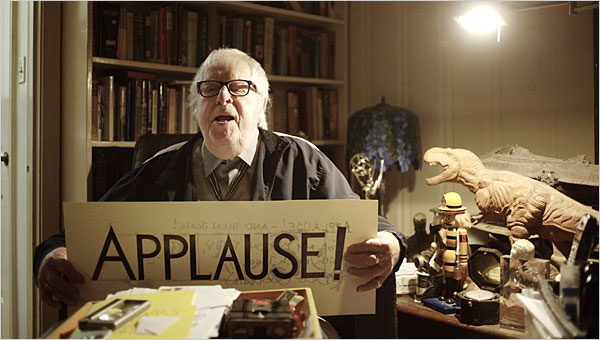

Ethan Pines for The New York Times

By Jennifer Steinhauer

Published: June 19, 2009

VENTURA, Calif. — When you are pushing 90, have written scores of famous novels, short stories and screenplays, and have fulfilled the goal of taking a simulated ride to Mars, what’s left? Ethan Pines for The New York Times “Bo Derek is a really good friend of mine and I’d like to spend more time with her,” said Ray Bradbury, peering up from behind an old television tray in his den.

Ethan Pines for The New York Times “Bo Derek is a really good friend of mine and I’d like to spend more time with her,” said Ray Bradbury, peering up from behind an old television tray in his den.

An unlikely answer, but Mr. Bradbury, the science fiction writer, is very specific in his eccentric list of interests, and his pursuit of them in his advancing age and state of relative immobility.This is a lucky thing for the Ventura County Public Libraries — because among Mr. Bradbury’s passions, none burn quite as hot as his lifelong enthusiasm for halls of books. His most famous novel, “Fahrenheit 451,” which concerns book burning, was written on a pay typewriter in the basement of the University of California, Los Angeles, library; his novel “Something Wicked This Way Comes” contains a seminal library scene.

Mr. Bradbury frequently speaks at libraries across the state, and on Saturday he will make his way here for a benefit for the H. P. Wright Library, which like many others in the state’s public system is in danger of shutting its doors because of budget cuts.“Libraries raised me,” Mr. Bradbury said. “I don’t believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries because most students don’t have any money. When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn’t go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years.”

Property tax dollars, which provide most of the financing for libraries in Ventura County, have fallen precipitously, putting the library system roughly $650,000 in the hole. Almost half of that amount is attributed to the H. P. Wright Library, which serves roughly two-thirds of this coastal city about 50 miles northwest of Los Angeles.

In January the branch was told that unless it came up with $280,000 it would close. The branch’s private fund-raising group, San Buenaventura Friends of the Library, has until March to reach its goal; so far it has raised $80,000.

Enter Mr. Bradbury. While at a meeting concerning the library, Berta Steele, vice president of the friends group, ran into Michael Kelly, a local artist who runs the Ray Bradbury Theater and Film Foundation, a group dedicated to arts and literacy advocacy. Mr. Kelly told Ms. Steele that he could get Mr. Bradbury up to Ventura to help the library’s cause.On Saturday, the two organizations will host a $25-a-head discussion with Mr. Bradbury and present a screening of “The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit,” a film based on his short story of the same name.

The fund-raiser’s financial goal is not a long-term fix. That would come only if property taxes crawl back up or voters approve a proposed half-cent increase in the local sales tax in November, some of which would go to libraries.

Fiscal threats to libraries deeply unnerve Mr. Bradbury, who spends as much time as he can talking to children in libraries and encouraging them to read.The Internet? Don’t get him started. “The Internet is a big distraction,” Mr. Bradbury barked from his perch in his house in Los Angeles, which is jammed with enormous stuffed animals, videos, DVDs, wooden toys, photographs and books, with things like the National Medal of Arts sort of tossed on a table.

“Yahoo called me eight weeks ago,” he said, voice rising. “They wanted to put a book of mine on Yahoo! You know what I told them? ‘To hell with you. To hell with you and to hell with the Internet.’

“It’s distracting,” he continued. “It’s meaningless; it’s not real. It’s in the air somewhere.”

A Yahoo spokeswoman said it was impossible to verify Mr. Bradbury’s account without more details.

Mr. Bradbury has long been known for his clear memory of some of life’s events, and that remains the case, he said. “I have total recall,” he said. “I remember being born. I remember being in the womb, I remember being inside. Coming out was great.”

He also recalled watching the film “Pumping Iron,” which features Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in his body-building days, and how his personal recommendation of the film for an Academy Award helped spark Mr. Schwarzenegger’s Hollywood career. He remembers lining his four daughters’ cribs with Golden Books when they were tiny. And he remembers meeting Ms. Derek on a train in France years ago.

“She said, ‘Mr. Bradbury.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She said: ‘I love you! My name is Bo Derek.’ ”

Ms. Derek’s spokeswoman, Rona Menashe, said the story was true. She said her client would like to see some more of Mr. Bradbury, too.

Mr. Bradbury’s wife, Maggie, to whom he was married for over five decades, died in 2003. He turns 89 in August.

When he is not raising money for libraries, Mr. Bradbury still writes for a few hours every morning (“I can’t tell you,” is the answer to any questions on his latest book); reads George Bernard Shaw; receives visitors including reporters, filmmakers, friends and children of friends; and watches movies on his giant flat-screen television.

He can still be found regularly at the Los Angeles Public Library branch in Koreatown, which he visited often as a teenager.

“The children ask me, ‘How can I live forever, too?’ ” he said. “I tell them do what you love and love what you do. That’s the story on my life.” -

An L.A. Institution Turns 75, Seeks Memories

(Client: Farmers Market)

An L.A. institution turns 75, seeks memories

In January, the Original Los Angeles Farmers Market will commence a year-long celebration of its 75th anniversary. To help keep things festive, Angelenos are being asked to share their stories, photographs and other memorabilia of the market, which will be used on “memory boards” throughout the year. The boards will be displayed at several locations within the market and also online at www.farmersmarketla.com.

In January, the Original Los Angeles Farmers Market will commence a year-long celebration of its 75th anniversary. To help keep things festive, Angelenos are being asked to share their stories, photographs and other memorabilia of the market, which will be used on “memory boards” throughout the year. The boards will be displayed at several locations within the market and also online at www.farmersmarketla.com.In the spirit of the moment, I’d like to offer up my own favorite Farmers Market memory:

When I was in my early 20s, my parents came to visit for Easter. The night before they flew in I was cleaning up after a shift at the bar I worked at and found $25 in the parking lot. Those were lean times for me and I was really happy to have the extra cash. After I picked up my folks at the airport, our first stop was Canter’s (my dad loves liver and onions), and then we swung by the Farmers Market. My father, whose birthday was the next day, was admiring the pies at Du-par’s. In a fit of sentimentality, I bought him one with the money I had found. When I gave it to him, he was so pleased. It was a small gesture, a blip on the family-moments radar, but something about it lingers in my mind as especially sweet.

– Jessica Gelt

-

Farmers Market: This Man Is Not bleeding, It’s Pie.

(Client: Farmers Market)

Being from Texas, anything involving country music and pie appeals to me. And four years in Los Angeles have taught me that our city seldom provides these joys in concert.My friends are probably tired of my lamentations. “Why is there no low-lit bar in an old train car where you can square dance in this town?” I once dragged a friend to the gay country-western bar Oil Can Harry’s, in Studio City, for line-dancing. There was no pie, but I did the Boot-Scootin’ Boogie beside a man in skin-tight pocketless white jeans. I thought it was great, but my companion was not as enthused.

When I invited all my friends to the Fall Festival at the Farmers Market at Fairfax and 3rd over the weekend, only two of them accepted. The rest missed out on pie in the face, baby goats, and western swing à la David Lynch.

This annual festival is L.A.’s ideal place to be a throwback. We were last-minute contestants in the ten-person pie-eating contest. The scarecrow/referee told us we had three minutes to eat a cherry pie from Du-Par’s, no hands allowed. Whoever ate the most would take first prize, a 40-dollar gift certificate to the market. One would think this would all be in good fun, but it was intense. There were children everywhere, screaming and closing in on the table. Some contestants had entire cheering sections. All I’d eaten that morning were rice cakes. I felt unprepared.

Few things compare to the moment when you plop your face into a cherry pie for the first time. A completely new sensation, and much colder than I expected. I had no strategy. It was incredibly loud, a news camera was pointed at the table, and I barely managed to swallow. After the three minutes were up, and I was a clear loser, the little girl standing behind me criticized my process.

“You didn’t need to stick your face in it so much,” she said.

“Well, isn’t it more fun that way?” I said.

“Fine,” she said, and walked away. Her dad won third place.

Champion status went to Jamie Donovan, from London. “I’ve never entered a food eating competition, and I think I found my calling in life,” he told me. “Damn good pie.”

Overly satiated, we made our way to the music via the petting zoo, where a baby kangaroo was sharing a pen with a duck, and two baby goats were enclosed with a donkey. Interesting curation.

The remainder of the evening was spent in a digestive haze listening to a local western swing band called the Lucky Stars. They may be my new favorite band. Steel guitar, trumpet, acoustic guitar, fiddle, drums, and a wagon wheel front and center onstage. These guys wear matching cowboy hats and shirts with tassels. They cover Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. And their fans know how to dance. My favorite dancer bore an uncanny resemblance to the Cowboy from Lynch’s Mulholland Drive.

My impression leaving this event was that everyone there, including myself, was giddy. Angelenos don’t know how country they are until they suddenly find themselves—what else—eating pie, listening to the steel guitar, and loving it.

—Yvonne Puig